Making Lines, Reading Sounds, Storying Climate Encounters

Making Lines and Drawing Sounds functions as a small interference in established practices of literacy with young children. It treats literacy otherwise. Drawing lines becomes an occasion to attend to the sounds and densities that emerge in collective drawings and in the multiple intersections of lines. Each meeting of lines produces the possibility of hearing new sounds—sounds that compose a language not yet known and experimentally made in the moment.

Children gather around crossings of long and short lines, oblique lines, dense and thin lines. Their fingers follow the marks and, as they trace the lines, they read their sounds. In these acts of reading, drawing extends into sound, generating a language that slowly begins to demand its own signs. Literacy is produced through acts of creation and correspondence that are not necessarily representational and even less oriented toward a predetermined end.

This is not a tame literacy. It is not grounded in prescribed notions of reading and writing, nor does it aim to produce “tame readers of a tame language” (Snaza, 2011, p. 8). Rather, the project takes up Snaza’s call to think language as “always already more and other than anthropomorphism—not conceptual or representational, but performative and musical” (Snaza, 2011, p. 9).

Treating literacy in this way opens possibilities for alternative childhoods. New actors emerge, agency is distributed, and mastery and dominion—particularly the dominion of language—are unsettled. In this disturbance, a possibility arises for rethinking the human itself.

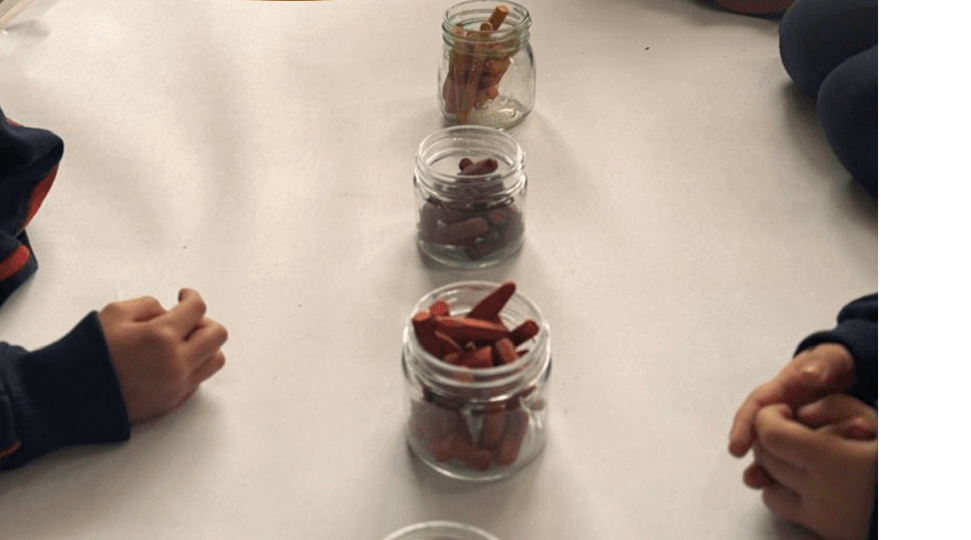

A large scroll of paper is placed on the floor

alongside greens, yellows, reds, oranges,

and muted browns that fill clear jars,

creating a visual language that resonates with our

ongoing forest walks and emerging encounters with leaves.

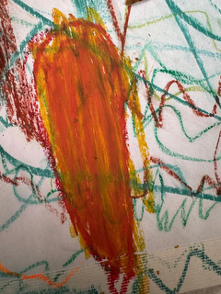

We lean in to draw undulating lines of sound.

The lines rise and fall, tracing peaks and valleys.

As the crayons move, so does the sound

—shifting with each gesture,

carried by the movement of the hand.

We wonder how we might write the sounds of leaves?

Drawing Sounds

Drawing sound begins with time. Each line the children make carries a kind of time signature—its length, weight, and rhythm often corresponding to the duration or intensity of the sound they hear. This temporality is difficult to perceive in still photographs alone; the lines flatten when separated from the movements and pauses that generated them. This is why we turn to animation and video, which allow the temporal qualities of the drawings to surface again. And while we are not following any formal system of musical notation, the children are nonetheless engaged in an embodied practice of annotating sound—one that experiments with tempo, volume, and pitch through the very act of drawing.

The awkward pauses at the peaks are where the children sustain, a slur connecting one sound to the next, carrying resonance from what came before.

Perhaps these gestures reflect how sound moves through and from our bodies—lively, brisk, and full of motion, in allegro.

Each line holds its tone in fermata—a note sustained—until it reaches a sharp peak or a plunging valley.

The whole of a sonic form sometimes shifts into staccato upon reading, punctuated and alive.

And everything here moves in cantabile—in a singing style.

These are articulations: intentional choices of audition made by the children,

carrying the weight of meaning from their perception of the world.

As the children draw, lines overlap other lines. The children pause, unsettled by the crossings.

He is drawing all over my drawing. –Vivian

The lines cannot touch. –Joaquin

Lines overlapping and crossing is met with hesitation. We offer questions:

- How are the lines allowed to touch, to cross, to fold over one another?

- What happens to the sounds of the leaves when the lines touch?

The questions linger and fold into the movement of crayon and sound. Each meeting of lines becomes a chance to hear new sounds that compose a language not yet known and experimentally created in the moment.

I draw big sounds on the paper so they can be heard more.

—Juanfer

The sounds we are drawing come together and make new sounds.

—Juan Mateo

I connected with many sounds to make one stronger.

—Alba

My sound is louder because I connected with the sound of all my friends.

—Joaquin

The lines begin to gather, to layer, to mark the density of sounds. The page holds not only individual gestures but the volume of many sounds together.

How might this density be read? Could it be a score to listen with? Or perhaps the drawing itself is the sound—its thickness, its crossings, its echoes?

The lines invite us to think of sound in the density, in the crossings that require many soundings at once.

Reading Sounds

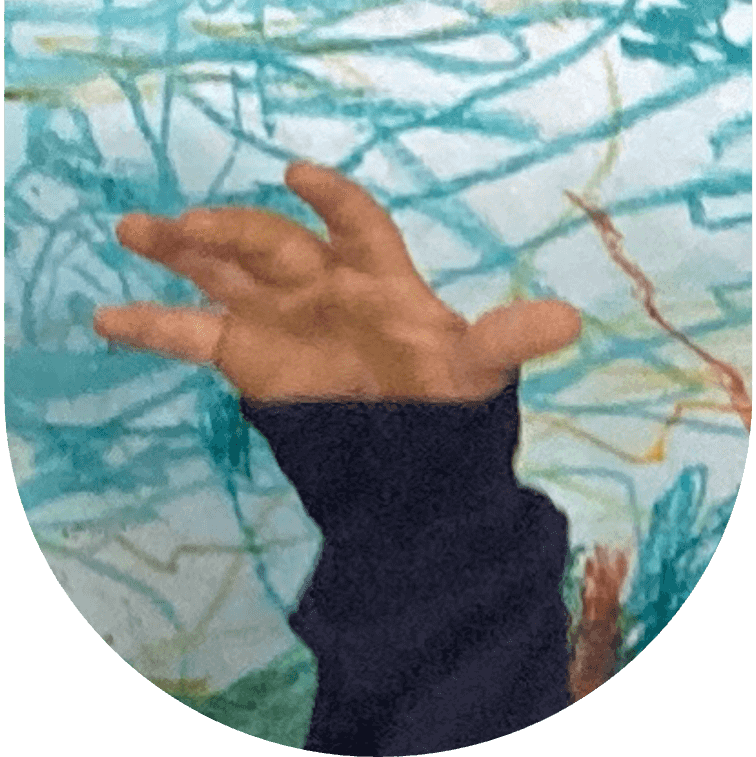

We gather around the panel to read sounds. Fingers follow the marks, tracing them into voice. The lines move fast and slow, with pauses and interruptions. They resist being read in isolation; they overlap, tangle, and lean on one another. These lines provoke us to voice them as a collective, all at once. Our fingers become conductors of a small orchestra, tapping a tempo, sustaining tones, drawing our voices along paths of fingers and lines across the paper.

The greens are a soft shhh.

The reds repeat tri, tri, tri.

Tri Tri Tri Tri Tri—Tri Tri Tri Tri Tri Tri Tri Tri

—Olivia M.

This sound is sharp like the razor leaf (paja).—Joaquin S.

Sh Shui Shwe Sssssh—JuanMa

This leaf is floating around in the forest.—Agustin

As our fingers return to the lines we have drawn, we notice: the lines carry rhythm, they follow a breath, they hold the memory of a leaf dancing in the wind and landing at the peak of a line.

Drawing and making sounds are ways of reading that help us pay attention to the movements, textures, and energies around us.

As we draw, we read and as we read we attach significance to signs that appear in the way fingers move across marks on a page, in a breath that rises and falls with the lines.

When we read in this way, we are creating a language. It is a language beyond grammar or sentence structures—one made from gestures, sounds, touches, and shared attentions. A language that helps us sense the world and understand it together. This is not a language created a-priori. It emerges in the drawing, shaped by lines, sounds, and the ways we meet them. Reading sounds goes beyond linking a noise to a shape, a line to a rhythm, a peak to staccato. The forms evoke something more. Sound, after all, is not a cacophony of noise without significance. These drawn marks, these traced gestures, become sonic objects—shapes that carry possibilities, memories, and presences. They begin to hold ontologies of their own: ways of being in the world through sound, through leaf, through line.

Resisting Sonic Isolation

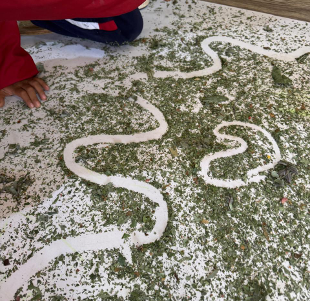

We create an undulating line of eucalyptus leaves that the children encounter in their walks. The shape invites the children in, as if to step inside the line they had traced before.

Only this time, instead of the conductor-like precision of fingers reading a single sound at a time, the children respond with their whole bodies. This marks a shift in our inquiry, as a line begins to gradate outward, moving toward the multiplicity of the leaves and perhaps resonating with the density of sounds held in the drawings.

The leaves immediately disrupt the sedimentation of lines that read sounds.

The leaves scatter the line, dispersing its order, resisting a fictional sonic isolation.

We imagine the leaves as rain falling on us. A different sound emerges as they drop—soft, scattered, insistent. As the rain covers us, the multitude of sounds comes to the fore once again.

The leaves scatter across the classroom floor forming clusters of leaves. Children trace the impressions of leaves and stories take form.

In these stories, many of the ideas we have been exploring weave together with new sounds, shapes, movements.

A long winding snake like shape is created as leaves moved into shape. Various sound iterations from previous experimentations are added to stories that narrate what happens to the land when rain finally comes. We pause and pay close attention to this snake shape of leaves.

The snake is coming

down from the mountain…

he is searching for a sound. –Alba

When the snake

arrives, it rains,

so it hides in

a cave.- Juanfer

In rain the snake

hides under green leaves.

–Olivia M.

The leaves turn green

when the snake walks on them.

That’s why the leaves make the sound sh.

–JuanMa & Olivia E.

The snake crawls on the leaves and turns them green.

–Rebbeca

The worms save the snake… because rain makes leaves heavy.

– Joaquin S.

I am blowing like the

wind so the leaves move.

—Joaquin

Multiple characters—snakes, rain, and leaves—populate our stories.

Voices rise and intertwine: a leaf hisses, a stream of leaves flowing out of a basket transforms into rain, and the leaves are also just leaves—rustling, forming, sounding the life of the characters—as the children compose together through gesture and sound.

Between the lines and the rustle of leaves, we encounter a language that does not fix itself in words. It carries stories of rain, of worms, of snakes, of paths. This language is alive through gesture, memory, and imagination.

The story that is created is far from being homogeneous. For some children, the snake seeks the sound of rain. For others, the snake is the sound, with its movement creating and searching for the very noise it makes. The children create a polyphony out of a single sound as it comes to mean differently for each child, generating a multiplicity of narratives. They multiply the threads of the story, unravelling and reweaving them. In doing so, they diversify the narrative, creating plural stories that grow and shift with each gesture and sound.

In Andean stories, the snake is tied to water, to rivers, to the pathways of rain. We notice the resonances with children’s stories and, in this, we connect our leaf world to Andean cosmologies.

The snake lingers as more than a story. It is a figure that moves across form, matter, and sound — inviting us to consider how we might stay with its undulations.

The serpentine figure becomes part of a larger weaving, where the language of forms meets sounds in a constant creative unfolding.

Following children’s designs, we set up a snake-like figure. Its face is formed in the language of acorns and bark. A long, slick green body extends across the space.

Click play to hear the sound of

feet and the sound of imagined rain.

These footprints look like a path and have different shapes. One is shaped like a heart and the others are like large mountains.- Agustine & Joaquin A.

As the snake transforms into scattered leaves, lines and shapes appear where feet and fingers create traces. The leaves carry impressions of movement.

We wonder who is moving through here.

We look for the sound the snake seeks.

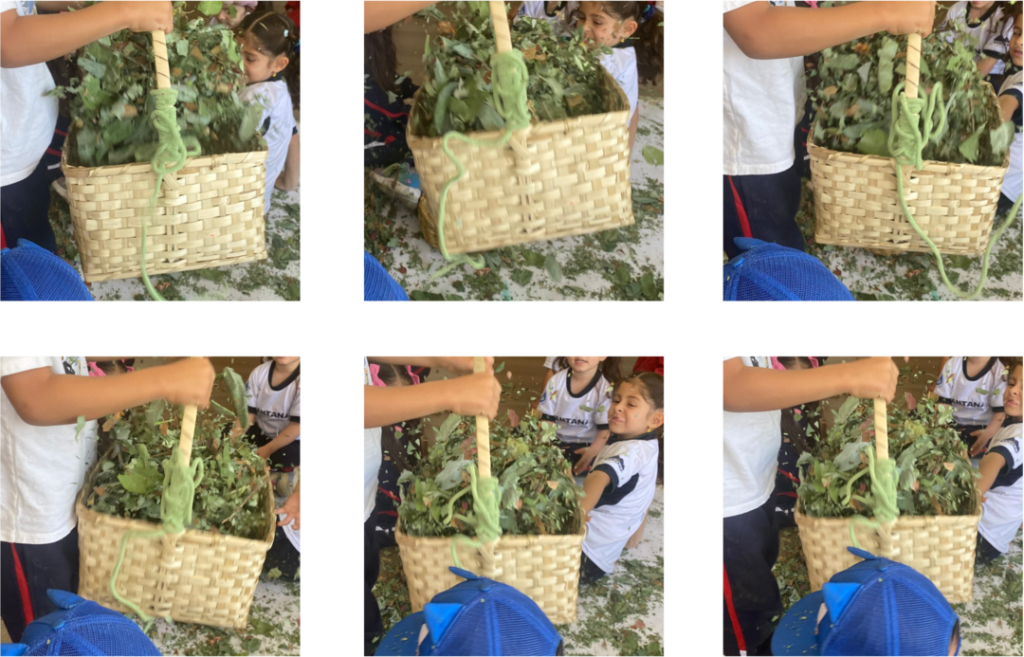

Juanfer shakes a basket filled with crunched-up leaves. The leaves fall as does an imagined rain.

I’m making it rain!—Juanfer

The rhythmic sound of leaf-rain invites the children to think of worms, which often appear after it has rained.

As the rain covers the traces

the snake stories shift.

Now the snake is buried

and the worms will come

to save the snake.—Joaquin A

It’s the worms crawling.

—Joaquin S

We are making this path

so the rain doesn’t fall on them.—Olivia

The path becomes both

trace and shelter, a way of moving

with the worms beneath the rain of leaves.

In this strand of inquiry, sounds that began as lines spread outward, becoming gradients of diverse stories that enwrap snakes and worms. They are also embodied by the children.

Leaf-rain falls around us, The snake searches for its sound, yet everything grows quiet once the source of the sound is found.

Stories continue to multiply. As the rain of broken leaves settles on us gently, prickly, speckling our white shirts green, we realize that we have become part of the snake’s quest. The sound we were seeking is now still. The leaves are resting on our bodies. It is quiet here. The sound feels as if it lives somewhere between us and the world beyond.

Through this journey, the children take up reading and writing—in ways that move beyond organized representational text and into the embodied, affective intensities of a lived, shared reality.

References

Snaza, N. J. (2011). Bewildering Education: Literature and the Human After Nietzsche [ProQuest Dissertations & Theses]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/874157363?pq-origsite=primo